Because pagan religions can be broadly described as spiritual beliefs which worship nature, it is reasonable that some persons believe that living in urban areas presents an obstacle to connecting with nature. One such pagan is Baz Bardoe who asserts that ‘the city is a warzone, and as in any warzone, one’s ability to fully explore individual potential is compromised’ (Cavandish & Conneelay 2012). However, some pagan authors argue that is an assumption and not a fact (Scarlett 2010). Furthermore, urbanism and technological advances should be regarded as part of the natural flow of things and not a divorce from them (Cunningham 2012). Ultimately, religion is about a personal spiritual connection. Therefore, there is no objectively correct way to practice paganism or any other religion. Instead, it is for each person to decide for themselves how they understand their religion and how to best engage with it.

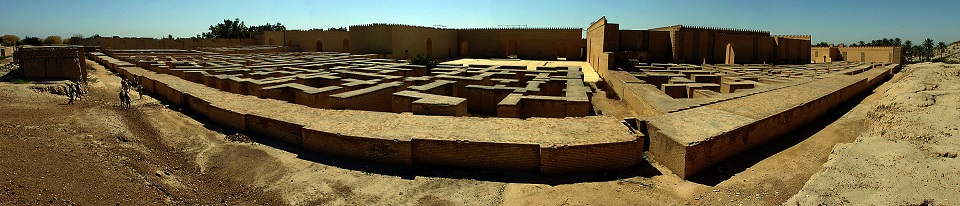

It has been asserted previously that the word ‘pagan’ comes from the Latin word paganus which means ‘country dweller’ (Marriam-Webster 2017; Cavendish & Conneeley 2012; Boin 2014). As such, some members of the pagan community affirm that living in a rural area and performing rituals in the wilderness are essential for an authentic pagan experience. However, Scarlett (2010) argues that this is simply a matter of personal preference and not a practice which is supported by archaeological evidence. Ancient Egyptian, Babylonian, Greek and Roman civilisations constructed and dwelled in cities which housed temples to pagan gods (Scarlett 2010) Furthermore, it was common for the citizens of these civilisations to have altars to their gods inside their houses (Scarlett 2010). This suggests that pagan religions did not traditionally shun urbanism.

Scott Cunningham (2012) develops this argument further and asserts that technology and technological advances cannot be divorced from magical practice. Wands, chalices, candles, tarot cards and magical recipes are all a product of technological advancement as none of these items occur naturally. Rather, all of these items products of human intervention into the natural world so as to create tools for our benefit. Therefore, even if a pagan moves to the country but lives in a permanent structure, uses electricity, has an internet connection or even lights a fire, they are still using technology to practice their craft. However, this should not be a cause for dismay because technology and innovation are not a divorce from the natural world but a continuation of it.

As Cunningham (2012) explains, the cotton shirt you wear began as a cotton plant which was nourished by the sun, soil and rainwater. The same can be said for any wooden, metal or plastic items that are used in rituals. All these items are fabricated from naturally occurring substances. They are not made from alien elements that do not occur naturally in nature. If it is accepted that magic is the practice of applied technology, then there is no contradiction between being pagan and following this path in an urban environment.

Finally, as Cavendish and Conneeley (2012) note, many of us are not indigenous people so our current homeland is not out ancestral homeland. Therefore, we must analyse what we mean when we discuss connecting to our ‘homeland’ or the ‘natural’ world. Because the vast majorly of Australians are not Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, we must all ask ourselves if engaging with our natural surroundings will bring us closer or further who what we consider to be our pagan beliefs.

Because paganism is a broad term which encompasses many spiritual paths, the information above may not be applicable in all situations. Ultimately, it is for each person to decide for themselves what makes sense to them and how they can best follow their spiritual path with integrity. All religious and spiritual sources are guides rather than instruction manuals regardless of how firmly they assert their position. Each person has their own consciousness, their own values and the right to freedom of religion. Therefore, the rewards or challenges of an individual’s pagan experience depend on their understanding of what constitutes paganism.

References

Boin, D 2014, ‘Hellenistic Judaism and the social origins of the Pagan-Christian debate’, Journal of Early Christian Studies, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 167-196, Project Muse, viewed 18 September 2017, DOI: 10.1353/earl.2014.0017

Cavendish, L & Conneeley, S 2012, Witchy Magic, Blessed Bee Publishing, Newtown, New South Wales

Cunningham, S 2012, Cunningham’s Magical Sampler, Llewellyn Worldwide, Woodbury, Minnesota

Marriam-Webster 2017, Origin and Etymology of Pagan, viewed 18 September 2017, <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pagan>

Scralett, C 2010, Urban Paganism: Pagan in the City & Ritual, The Pagan and the Pen, viewed 25 April 2018, < https://thepaganandthepen.wordpress.com/2010/02/03/urban-paganism-pagan-in-the-city-ritual/>